Popular Highlights

When only a watchmaker will do

Restoration of Omega Jump Seconds Clock

|

When Only a Watchmaker Will Do Swiss Trained, Omega Recognized Provider |

|

|||

|

It was easy to service a timepiece when parts were available off the shelf. However, that is becoming increasingly rare. Mainsprings for vintage pieces are no longer made, and I cannot even get another run of mainsprings I had custom made in Switzerland for the Waltham CDIA and 37500 Elgin/Hamilton Aircraft clocks. Many workers routinely reuse the 70 year old spring they find in the clock. Worse, they may offer to install new/old stock mainsprings. These are blue carbon steel springs. No one has made these for 60 years and they can either "set" or have started to corrode. They can break catastrophically damaging the instrument. A new blue steel spring is worse than the used one because while the used one is fatigued, the 60 year old unused spring often shatters at full power within a year or so with devastating results.

New Stainless Steel and set blue steel springs (37500)

Shattered and rusted 37500 blue steel springs

Custom Swiss made SS ("unbreakable" ) 37500 Springs Balance staffs are another issue. Years ago I started buying up aircraft clock balance staffs from the material houses because I had learned that vintage balance staffs were no longer being made (same with jewels). I have staffs for everything from the 37500 and CDIA to the Jaeger LeCoultre and Mathy Tissot Type 12. When a worker does not have the part, he will frequently hope to "get by" by using the broken part, or if not a watchmaker, he may not even recognize it. I recently had an MSR Z8 (sold under various names such Thommen, Longines, etc.) that was sold to a customer and even had a recent FAA cert on it by the company that sold it. It did not keep time. Reason was the balance staff upper pivot was worn to a nub from lack of lubrication. I quoted the job. Looked at my stock, no staff. Called a couple material houses, no stock. So, I made the staff and held to my quote even though I charge twice as much for a custom staff as for a replacement. But I missed the quote. So it goes.

MSR Z8 with custom staff. Aesthetics are meaningless if the piece is not functional Bear in mind that the MSR Z8 is a "modern" movement, manufactured into the 1990s. But replacement parts for mechanical aircraft clocks are obsolete and many "breakable" parts are simply unavailable. Cracked jewels that are allowed to remain are a major source of lubrication problems. The crack draws the oil away via capillary action. These must be replaced or the work refused. Worse, a damaged jewel can cut the pivot itself impacting timekeeping and even cutting straight through with the expected results. Unfortunately, someone not trained in watch service will not know enough to look or may not even possess a microscope to aid in inspection. And if he did not stock up on jewels or purchase the equipment for their replacement ......

Extreme example of cracked plate set jewel requiring traditional replacement technique shown here

Some of the friction jewel inventory

Equipment used for precise replacement of friction jewels

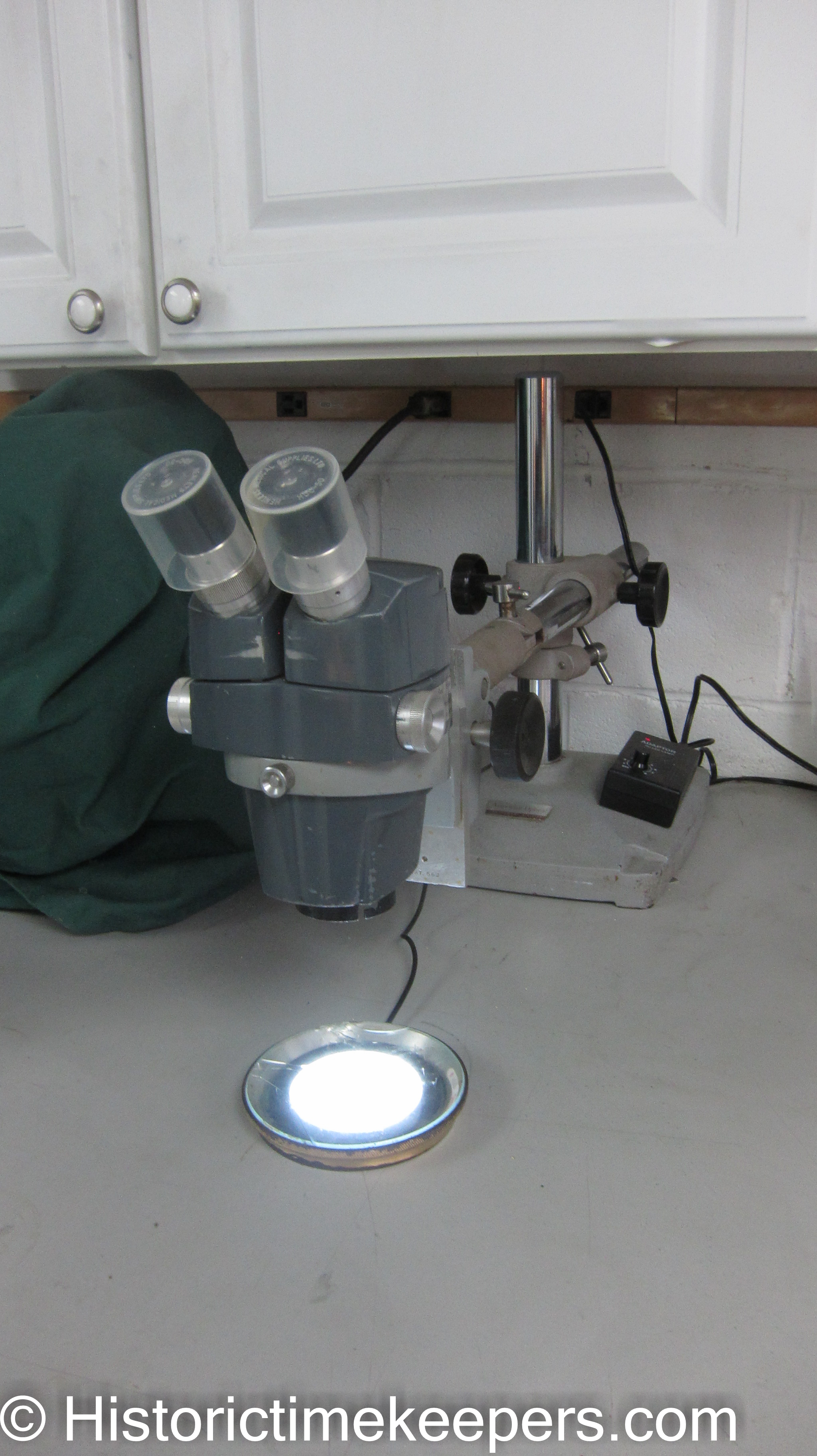

Good high powered optics for inspection

To learn more about the usefulness of microscopes, visit our Microscopes in Watchmaking page. Then comes the problem of an important timepiece for which parts are not available. I often encounter Jaeger LeCoultre aircraft clocks with broken winding stems or winding wheels. These are broken because the vintage Swiss clocks "wind backwards" and have no clutch. I have seen pliers marks on the knob from attempts to wind them when the user was unaware of this fact.

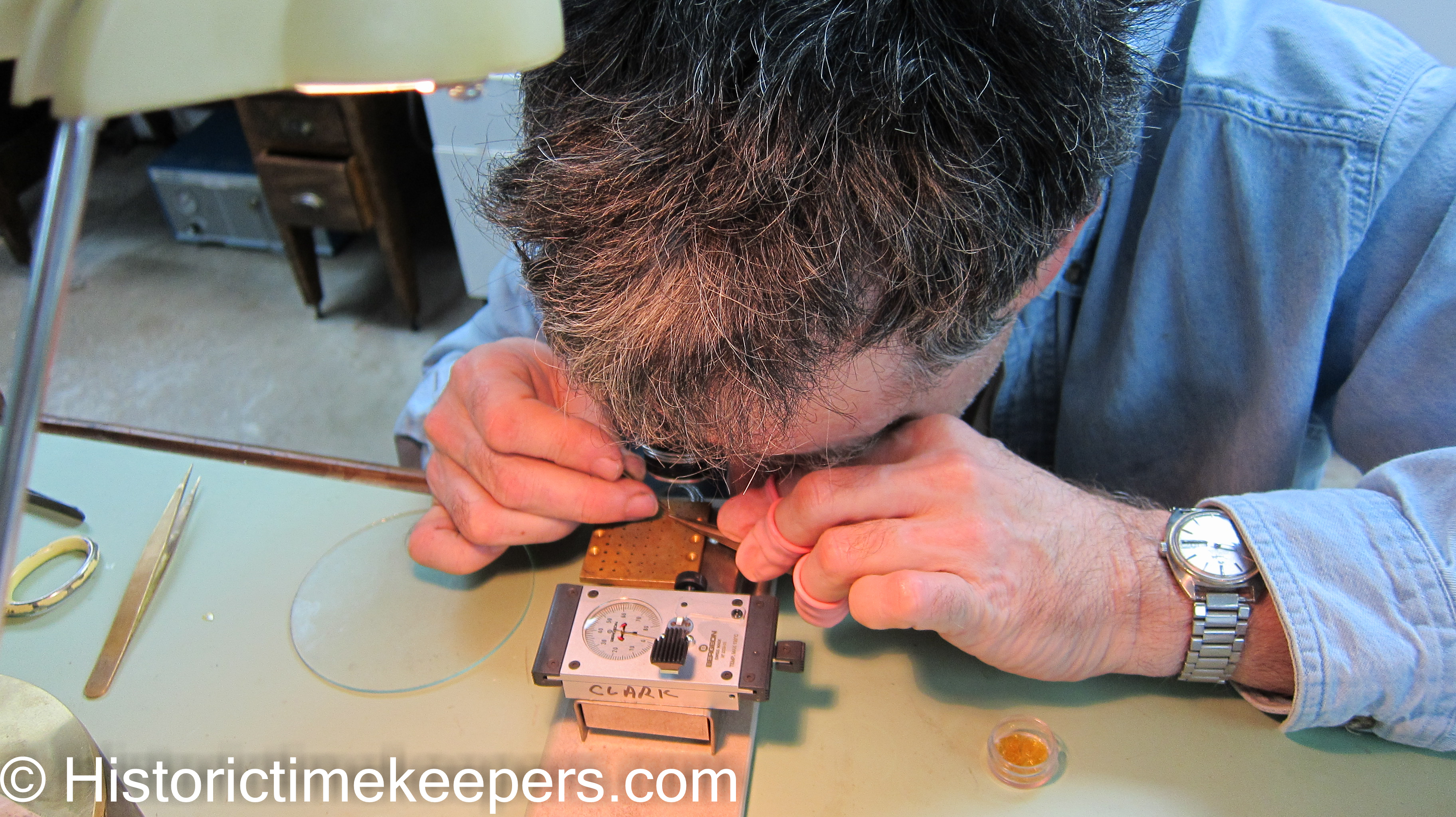

Verifying manufactured Jaeger stem against sample Since these parts are not available they have to be made. While lathe work is not rocket science, it does require skill and experience to measure, plan and execute the work; including knowing how to make the proper gear cutter to mill the teeth of gears and pinions when that cutter is not already part of the shop's library.

Finally comes the most important reason for a watchmaker. Performance. Everything previously mentioned is just preparation. Reassembling an instrument and hearing it tick means nothing to a watchmaker. He uses timing instruments to assess the performance (beat, amplitude and rate deviations across positions) of the piece. If it is not within spec, he knows how to make the adjustments (no, this is NOT moving the fast/slow regulator) to bring it within specifications. Especially for vintage pieces with steel balance springs, it is vital that the movement be properly demagnetized if precision timing is to be accomplished.

Clean work area and modern timing equipment

A modern demagnetizer is essential if precision timing is expected from vintage teimpieces with steel balance springs The timing instrument is a critical task master and a disciplined watchmaker accepts it's judgment. Most of the faults listed above would be immediately apparent during testing and a watchmaker will go back and determine and apply the needed corrections. HTI tests for a minimum of 7 days. The equipment needed for this work is expensive and may only be used 6 times a year (the escapement adjusting tool is 500 CHF and if I use it 4 times a month that is a lot). A specific pinion cutter may be used once every two years. But it is all needed to be at hand.

Using the escapement tool to make precise adjustments to the pallet jewels in preparation for precision timing But even more important is the training in the theory and execution of precision timekeeping. It is not something that can be self taught. I was fortunate enough to be invited to Switzerland for a year of advanced training. Then there is experience (in my case, 40 years) and judgment. Here is an example of a very uncommon instrument; a late 1930s RAF Swiss Time of Trip clock. The movt was of a lower quality maker and not signed other than marked as of Swiss manufacture. The issue was I could not uncase the piece because the screw retaining the chrono pusher was rusted and the head stripped.

Screw rusted and head deformed

Arbor crosspinned to maintain knob orientation There were two obvious considerations. The knob and case must be preserved. There was no room to mount the piece into the vise and mill the screw out. I COULD make the operating arbor. In consultation with the owner, I parted the arbor just below the knob, allowing me to move on with the job. I then dissolved what was left of the steel arbor and screw still in the knob, leaving the knob as original. I then made the operating arbor. The complete story of this piece can be found here.

Final result. Knob preserved, manufactured arbor. Grub screw rather than cross pin. The point is, micromachining is but only one essential element of aircraft clock service and restoration. A little sexier, but really akin to ensuring the surfaces are chemically clean before applying lubricants. If you want your timepiece to perform as intended, ask about the training of the worker. And at Historic Timekeepers, Inc., you will receive a summary evaluation of your instrument's performance that provides the same information used by Swiss service centers to assess the quality of their work. Finally, a word of caution: I do not do work for other companies NOR do I sell my stainless steel "unbreakable" mainsprings to others. Remember, precision timing literally starts with a good mainspring. If I have to reuse your old mainspring because there is nothing available I will tell you BEFORE doing the work. If it prevents precision results, I will discuss this with you before sending the final bill. The biggest problem for the prospective customer is to determine if the worker can actually get results. My site serves two purposes, first to demonstrate to prospective customers that I do the work cleanly and precisely without guesswork. The other purpose is to provide some guidance to those younger than me in their efforts to become skilled at restoration work.

|

||||